The Hindu, Sunday February 3rd, 2008

Indian perspective

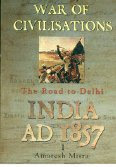

Amaresh Misra’s book shed new light on the 1857 Revolt

Amaresh Misra is a film critic turned war analyst. The guy who acquitted himself creditably writing about films most read about, and only a few saw, is busy showing another facet of his personality. He has just authored an unexpected tome on the Revolt of 1857 or, as some call it, the First War of Independence. Amaresh calls it “the world’s first holocaust”. Brought out by Rupa, War of Civilisations: The Road to Delhi and India AD 1857 is not the first time Amaresh is walking down the history lane though.

Interest in history

Having already penned a biography of Lucknow in Lucknow: Fire of Grace and a biography of Mangal Pandey, Amaresh is well equipped. “My first book was on history. My interest in history run parallel to my love for films,” says the Mumbai-based Amaresh, adding, “I always admired the work of historians like Professor Irfan Habib and others, but they don’t ask new questions. My stint as a journalist came in handy. Since 1957, no Indian has written a comprehensive account of the Revolt. Indian historians have done a limited work. In the West Christopher Hubert wrote The Great Rebellion. William Dalrymple has also written. But I always felt the need to write of 1857 from the Indian perspective.”

He speaks like an academic when he speaks about 1857. For fleeting moments though, the cineaste in him comes to the fore. Then he shows the insight of a seasoned media man.

“1857 was the world’s first holocaust, resulting in the loss of an estimated 10 million Indians. The Revolt cannot be confined to just North India. There were widespread risings in Gujarat, the modern-day Pakistan, North Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Orissa, Chhattisgarh, Bengal, Assam, even modern-day Bangladesh. I don’t know why nobody talks of regional uprisings. No one attempted to put together a pan Indian picture. This book tells the reader that from Gilgit to Madurai, from Manipur to Maharashtra, not one area was unaffected. It was amazingly well coordinated.”

He is not through with surprises. “Contrary to common perception, important roles were played by the likes of Azimullah. In Ayodhya, at the site where the Babri Masjid was demolished, Mahant Ramdas and Maulavi Amir Ali, as well as Shambhu Prasad Shukla and Achchan Khan, two religious Hindus and two religious Muslims, were hanged side by side.”

He reveals that Zafar looked at his subjects as one, irrespective of religion. And in 1857, orthodox Chitpavan Brahmin leaders like Nana Saheb opened their proclamations with Islamic invocations while Begum Hazrat Mahal and Khan Bahadur Khan issued direct appeals to Hindus in the name of Lord Ram and Krishna.

Southern ripples

Similarly, Amaresh reveals that the Revolt had more than a ripple across the Vindhayas. “In Madras, at a place called Vaniyambadi, the 8th Madras Cavalry rose. Elsewhere, led by Thevar-Vellala sepoys, several 37th Madras infantry men deserted. I have discovered that 8th Madras Cavalry revolted in October 1857. It was disbanded but the British suppressed the news. There were desertions from Madras Infantry in Hong Kong, Singapore, Rangoon.”

Through with the unheard? Wait, there is more to come from Amaresh. “Bahadur Shah Zafar was sent to Rangoon and the Burmese king was deported to Satara in Maharashtra!”

He continues, “Western authors have tended to see Indian characters as caricatures. Stereotypes abound. They don’t care to say that Azimullah was like James Bond. He was sleeping with the enemy but getting information out. He was the mastermind behind 1857.”

Open subject

He believes earlier historians often just reproduced the existing works. “No chapter had been written from the Indian perspective. They did not find the Revolt interesting or challenging. But it is still an open subject.”

So, why did he dare to tread where others had feared to walk?

“Now there is a wealth of information available in Urdu books, Persian records. Then some new British sources have been revealed, confidential files have been opened. It is a historian’s job to look at unconventional data, go beyond the labour report, the road survey report, etc. He has to see the links.

“If a British official was building a road in 1857 in Awadh, he faced a labour crunch. He researched into the labour conditions, made an estimate of the number of people missing resulting in shortage. It was based on his own impromptu immediate census. Everywhere different officials mentioned the same figures.

“I found an interesting document in a general post office go-down in Lucknow where a British officer wrote to his colleague saying he had 20 lakh unopened envelopes addressed to people belonging to Awadh. These people could not be found.”

Painstaking effort

It took Amaresh five years of work to put together this painstaking work.

“I shifted base to Mumbai in 2003 and was involved with a couple of film projects. Around 2004 I realised that 2007 would mark 150 years of the Revolt, so I increased my pace and the film projects went to the backburner. Originally I had a 600-page book in mind. But it kept growing.” And how!

Amaresh Misra’s book shed new light on the 1857 Revolt

Amaresh Misra is a film critic turned war analyst. The guy who acquitted himself creditably writing about films most read about, and only a few saw, is busy showing another facet of his personality. He has just authored an unexpected tome on the Revolt of 1857 or, as some call it, the First War of Independence. Amaresh calls it “the world’s first holocaust”. Brought out by Rupa, War of Civilisations: The Road to Delhi and India AD 1857 is not the first time Amaresh is walking down the history lane though.

Interest in history

Having already penned a biography of Lucknow in Lucknow: Fire of Grace and a biography of Mangal Pandey, Amaresh is well equipped. “My first book was on history. My interest in history run parallel to my love for films,” says the Mumbai-based Amaresh, adding, “I always admired the work of historians like Professor Irfan Habib and others, but they don’t ask new questions. My stint as a journalist came in handy. Since 1957, no Indian has written a comprehensive account of the Revolt. Indian historians have done a limited work. In the West Christopher Hubert wrote The Great Rebellion. William Dalrymple has also written. But I always felt the need to write of 1857 from the Indian perspective.”

He speaks like an academic when he speaks about 1857. For fleeting moments though, the cineaste in him comes to the fore. Then he shows the insight of a seasoned media man.

“1857 was the world’s first holocaust, resulting in the loss of an estimated 10 million Indians. The Revolt cannot be confined to just North India. There were widespread risings in Gujarat, the modern-day Pakistan, North Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Orissa, Chhattisgarh, Bengal, Assam, even modern-day Bangladesh. I don’t know why nobody talks of regional uprisings. No one attempted to put together a pan Indian picture. This book tells the reader that from Gilgit to Madurai, from Manipur to Maharashtra, not one area was unaffected. It was amazingly well coordinated.”

He is not through with surprises. “Contrary to common perception, important roles were played by the likes of Azimullah. In Ayodhya, at the site where the Babri Masjid was demolished, Mahant Ramdas and Maulavi Amir Ali, as well as Shambhu Prasad Shukla and Achchan Khan, two religious Hindus and two religious Muslims, were hanged side by side.”

He reveals that Zafar looked at his subjects as one, irrespective of religion. And in 1857, orthodox Chitpavan Brahmin leaders like Nana Saheb opened their proclamations with Islamic invocations while Begum Hazrat Mahal and Khan Bahadur Khan issued direct appeals to Hindus in the name of Lord Ram and Krishna.

Southern ripples

Similarly, Amaresh reveals that the Revolt had more than a ripple across the Vindhayas. “In Madras, at a place called Vaniyambadi, the 8th Madras Cavalry rose. Elsewhere, led by Thevar-Vellala sepoys, several 37th Madras infantry men deserted. I have discovered that 8th Madras Cavalry revolted in October 1857. It was disbanded but the British suppressed the news. There were desertions from Madras Infantry in Hong Kong, Singapore, Rangoon.”

Through with the unheard? Wait, there is more to come from Amaresh. “Bahadur Shah Zafar was sent to Rangoon and the Burmese king was deported to Satara in Maharashtra!”

He continues, “Western authors have tended to see Indian characters as caricatures. Stereotypes abound. They don’t care to say that Azimullah was like James Bond. He was sleeping with the enemy but getting information out. He was the mastermind behind 1857.”

Open subject

He believes earlier historians often just reproduced the existing works. “No chapter had been written from the Indian perspective. They did not find the Revolt interesting or challenging. But it is still an open subject.”

So, why did he dare to tread where others had feared to walk?

“Now there is a wealth of information available in Urdu books, Persian records. Then some new British sources have been revealed, confidential files have been opened. It is a historian’s job to look at unconventional data, go beyond the labour report, the road survey report, etc. He has to see the links.

“If a British official was building a road in 1857 in Awadh, he faced a labour crunch. He researched into the labour conditions, made an estimate of the number of people missing resulting in shortage. It was based on his own impromptu immediate census. Everywhere different officials mentioned the same figures.

“I found an interesting document in a general post office go-down in Lucknow where a British officer wrote to his colleague saying he had 20 lakh unopened envelopes addressed to people belonging to Awadh. These people could not be found.”

Painstaking effort

It took Amaresh five years of work to put together this painstaking work.

“I shifted base to Mumbai in 2003 and was involved with a couple of film projects. Around 2004 I realised that 2007 would mark 150 years of the Revolt, so I increased my pace and the film projects went to the backburner. Originally I had a 600-page book in mind. But it kept growing.” And how!

Comments